Choosing Wood for Paintings

The purpose of this article is to present the artist choices to follow in selecting a wood surface to use for painting. There are several types of panels and species involved in this decision, and it is easy to become confused by the varieties that exist.

Why Choose Wood?

First of all let us examine why we might choose wood in the first place. The types of materials often selected for two-dimensional paintings are wood, metal, stretched canvas, and synthetic panels. Wood has historical significance in dating back to ancient paintings hundreds of years old. The condition of many solid wood panels from medieval times in particular is extraordinary. Its strength, availability, and stability have much to offer the artist compared to other options. Although metal such as copper is more permanent, wood is absorbent, can weigh less, cost less, and still offer sufficient firmness of support. A firm support does offer a different response to the marks the artist makes than will a flexible canvas, which is an excellent surface for some applications, but wood is stronger, not textured, and less flexible; something required for some mediums.

A fairly recent manufactured product has appeared called acrylonitro-butyl styrene (ABS.) This is a synthetic plastic surface often used for outdoor signs, and has grown in favor among some painters for its ease of use, mainly being light weight and to not require priming. They are rather thin in width, needing extra support, and may bend under their own weight, although water will not affect them. Its long-term durability is also not absolutely certain. My own experiments with it have proven less than satisfactory, but I still hold a curiosity towards it. Ultimately, I feel wood performs as well or better in most cases as any other option when properly prepared.

Wood does have some disadvantages for painting as well. The most significant concern is its possible negative reaction to high levels of moisture. Increases in relative humidity, or the use of aqueous mediums can cause the cellulose fibers of wood to swell and the panel to distort into a cupped or twisted shape as it absorbs moisture. Other defects can appear over time as well such as cracks or splits.

Types of Wood Panels

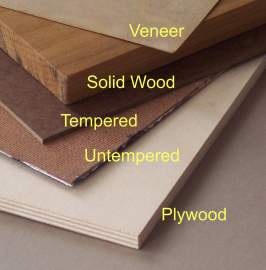

There are essentially three options one could make picking wood: solid wood, plywood, and composite fiberboard panels. Solid wood is a sliced plank right from the tree itself. Plywood is a layered sheet of thin veneer with a core made of different types of wood material. Composite panels are engineered sheets made from residual sawdust and resin based adhesives.

Solid Wood

The ideal choice for solid wood to use for direct painting is one that is somewhat absorbent, has low a shrinkage ratio, and is relatively low in acidity. Hardwood species are the best qualifiers for these specifications, although not all types meet these requirements. Trees are classified as either hardwood or softwood, depending upon, interestingly enough, the type of leaf they grow. Softwood conifers are always very acidic, but some hardwoods can be also, like oak. Some hardwoods are also quite soft, even softer than most softwoods. Balsa wood is classified as a hardwood, for example. As a result, it is not possible to simply say you should always choose hardwood for painting; it depends on the type. Some of the best overall hardwoods for painting are ash, birch, cottonwoods, mahogany, or maple. Even among these, there are certain varieties that are better choices than others of the same species. Something else to think about is selecting heartwood rather than sapwood. Heartwood is the older center section of a tree that is more resistant to decay. Other considerations to make are to avoid any contrast in the grain pattern texture, look for surface defects like knots, and how some species are darker than others.

Why Choose Wood?

First of all let us examine why we might choose wood in the first place. The types of materials often selected for two-dimensional paintings are wood, metal, stretched canvas, and synthetic panels. Wood has historical significance in dating back to ancient paintings hundreds of years old. The condition of many solid wood panels from medieval times in particular is extraordinary. Its strength, availability, and stability have much to offer the artist compared to other options. Although metal such as copper is more permanent, wood is absorbent, can weigh less, cost less, and still offer sufficient firmness of support. A firm support does offer a different response to the marks the artist makes than will a flexible canvas, which is an excellent surface for some applications, but wood is stronger, not textured, and less flexible; something required for some mediums.

A fairly recent manufactured product has appeared called acrylonitro-butyl styrene (ABS.) This is a synthetic plastic surface often used for outdoor signs, and has grown in favor among some painters for its ease of use, mainly being light weight and to not require priming. They are rather thin in width, needing extra support, and may bend under their own weight, although water will not affect them. Its long-term durability is also not absolutely certain. My own experiments with it have proven less than satisfactory, but I still hold a curiosity towards it. Ultimately, I feel wood performs as well or better in most cases as any other option when properly prepared.

Wood does have some disadvantages for painting as well. The most significant concern is its possible negative reaction to high levels of moisture. Increases in relative humidity, or the use of aqueous mediums can cause the cellulose fibers of wood to swell and the panel to distort into a cupped or twisted shape as it absorbs moisture. Other defects can appear over time as well such as cracks or splits.

Types of Wood Panels

There are essentially three options one could make picking wood: solid wood, plywood, and composite fiberboard panels. Solid wood is a sliced plank right from the tree itself. Plywood is a layered sheet of thin veneer with a core made of different types of wood material. Composite panels are engineered sheets made from residual sawdust and resin based adhesives.

Solid Wood

The ideal choice for solid wood to use for direct painting is one that is somewhat absorbent, has low a shrinkage ratio, and is relatively low in acidity. Hardwood species are the best qualifiers for these specifications, although not all types meet these requirements. Trees are classified as either hardwood or softwood, depending upon, interestingly enough, the type of leaf they grow. Softwood conifers are always very acidic, but some hardwoods can be also, like oak. Some hardwoods are also quite soft, even softer than most softwoods. Balsa wood is classified as a hardwood, for example. As a result, it is not possible to simply say you should always choose hardwood for painting; it depends on the type. Some of the best overall hardwoods for painting are ash, birch, cottonwoods, mahogany, or maple. Even among these, there are certain varieties that are better choices than others of the same species. Something else to think about is selecting heartwood rather than sapwood. Heartwood is the older center section of a tree that is more resistant to decay. Other considerations to make are to avoid any contrast in the grain pattern texture, look for surface defects like knots, and how some species are darker than others.

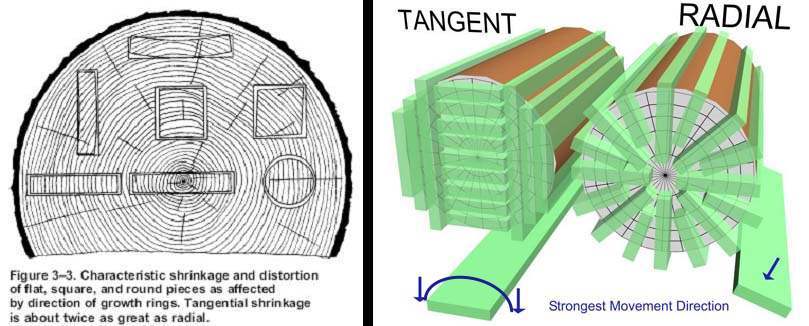

How solid wood is cut can greatly affect how it reacts to moisture. Wood planks in most mills or warehouses are cut tangentially ("flat cut",) which gives the least amount of waste. If you looked at the end (not the sides) of a plank of solid wood cut in this manner, you would see how the grain arches toward the center. This illustrates how the wood will curl as the fiber absorbs water, distorting into an arched shape. The more vertical those endgrain rings are, the less likely it is that the wood will distort. A radial or "rift" cut will give you a better quality panel, but causes more waste from the log so it is less common and expensive. If you decide to paint on a flat cut panel anyway, apply paint to the outer side that bends out in relation to that endgrain arch (called an open grain) rather than the side that curls in (convex.) This will put less destructive force on the paint surface should it warp later on. In a local museum, I have seen a large oil painting from the 16th century on solid wood roughly ¾ inch thick with about a ½ inch curl in the center, but generally speaking a thicker panel is less likely to warp. Smaller pieces also, up to about one foot square or so, tend to warp less than larger panels.

Solid wood can be limited in size options to some degree. Widths of six or twelve inches are common, with a depth of about ½ to ¾ of an inch, and lengths of four or eight feet. The size of the tree trunk itself is the limiting factor for a single plank; although, panels can be constructed to a larger size by gluing several small planks together (image a large heavy conference table, for example.) This can cause some surface irregularities, and increase the chance of the panel to split or break between the seams.

Up until about 100 years ago wood was sold by weight, but since green wood is heavier, a new standard was developed for selling wood by the foot in cubic units, called "board foot," which is equal to 144 cubic inches. The example formula would be (in inches) thickness x length x width / 144 = number of board feet.

Solid wood can be limited in size options to some degree. Widths of six or twelve inches are common, with a depth of about ½ to ¾ of an inch, and lengths of four or eight feet. The size of the tree trunk itself is the limiting factor for a single plank; although, panels can be constructed to a larger size by gluing several small planks together (image a large heavy conference table, for example.) This can cause some surface irregularities, and increase the chance of the panel to split or break between the seams.

Up until about 100 years ago wood was sold by weight, but since green wood is heavier, a new standard was developed for selling wood by the foot in cubic units, called "board foot," which is equal to 144 cubic inches. The example formula would be (in inches) thickness x length x width / 144 = number of board feet.

Plywood

Sheets of plywood make an excellent choice for painting. It offers a larger size than solid panels, and weighs less by volume than solid or fiberboard panels. Commercial plywood can be assembled in different ways, identified by the interior core construction. They are made of single-ply front and back sheets of veneer (not necessarily the same type or quality) and a thick wood core. That core can be made of several veneer layers (sometimes referred to as overlay,) composite fiberboard, solid planks, or a combination of these. Veneer cores are the most common, can be prone to have the most defects with void areas inside, and be made of lower quality softwood. Fiberboard (typically MDF) makes a very strong core, but at a cost of more weight. High density plywood (HDP) is typically only offered in birch or maple.

A, B, C, or D letters are sometimes placed to help identify the intended use of plywood: marine, interior, exterior, or structural grade. Interior or sometimes marine grade can have the least amount of cosmetic defects. Sometimes the letters appear in combination (AC) referring to the front and back side quality. Grade A should signify no knots or filled-in patches. Marine grade is typically (not always) of the best quality (often mahogany,) since it should have no voids inside, but is limited to the types of wood that would perform well when it sits in water. However, sometimes "marine" qualifies just by the resins used, and can be made of low quality wood and be very acidic. Exterior or structural grades are generally of the poorest quality, since strength is more important to their application than appearance. Sometimes a number is added in the labeling to designate exposure to weather: 1 all weather conditions, or 2 for indoor only. Most plywood is glued together using polyurethane and/or formaldehyde resins, but also starches or hide glue could be used for special applications.

It is not too difficult to assemble your own veneer plywood. Machine-cut veneer is very thin and easily scored with a utility knife. Alternating the direction of grain in each layer adds strength to the panel, and three or five layers makes a very strong product, although cutting can be problematic. A thin single layer of veneer glued to fiberboard also performs well and resists warping, but be sure and equalize the tension by gluing a similar sheet to the back with grain running in the same direction. PVA adhesives work well, hide glue or starch is even better. Veneer comes in rolls of 1, 2, or 4-foot widths and various lengths. It can be straightened with low heat or steam. Different cuts are available with veneer as with solid panels. In addition to flat or quarter-swan, there are rotary or rift cuts. Rotary cuts spin around the diameter of the log, and are the most common. Rift or Quarter-sawn cut options offer the same benefits as in solid panels, but being thin flexible sheets makes that less of a concern. Essentially veneer is very thin solid wood, and needs added support. I have made finished paintings on a single veneer sheet, but they are finished when mounted to a thicker support or lighter cradled frame.

Sheets of plywood make an excellent choice for painting. It offers a larger size than solid panels, and weighs less by volume than solid or fiberboard panels. Commercial plywood can be assembled in different ways, identified by the interior core construction. They are made of single-ply front and back sheets of veneer (not necessarily the same type or quality) and a thick wood core. That core can be made of several veneer layers (sometimes referred to as overlay,) composite fiberboard, solid planks, or a combination of these. Veneer cores are the most common, can be prone to have the most defects with void areas inside, and be made of lower quality softwood. Fiberboard (typically MDF) makes a very strong core, but at a cost of more weight. High density plywood (HDP) is typically only offered in birch or maple.

A, B, C, or D letters are sometimes placed to help identify the intended use of plywood: marine, interior, exterior, or structural grade. Interior or sometimes marine grade can have the least amount of cosmetic defects. Sometimes the letters appear in combination (AC) referring to the front and back side quality. Grade A should signify no knots or filled-in patches. Marine grade is typically (not always) of the best quality (often mahogany,) since it should have no voids inside, but is limited to the types of wood that would perform well when it sits in water. However, sometimes "marine" qualifies just by the resins used, and can be made of low quality wood and be very acidic. Exterior or structural grades are generally of the poorest quality, since strength is more important to their application than appearance. Sometimes a number is added in the labeling to designate exposure to weather: 1 all weather conditions, or 2 for indoor only. Most plywood is glued together using polyurethane and/or formaldehyde resins, but also starches or hide glue could be used for special applications.

It is not too difficult to assemble your own veneer plywood. Machine-cut veneer is very thin and easily scored with a utility knife. Alternating the direction of grain in each layer adds strength to the panel, and three or five layers makes a very strong product, although cutting can be problematic. A thin single layer of veneer glued to fiberboard also performs well and resists warping, but be sure and equalize the tension by gluing a similar sheet to the back with grain running in the same direction. PVA adhesives work well, hide glue or starch is even better. Veneer comes in rolls of 1, 2, or 4-foot widths and various lengths. It can be straightened with low heat or steam. Different cuts are available with veneer as with solid panels. In addition to flat or quarter-swan, there are rotary or rift cuts. Rotary cuts spin around the diameter of the log, and are the most common. Rift or Quarter-sawn cut options offer the same benefits as in solid panels, but being thin flexible sheets makes that less of a concern. Essentially veneer is very thin solid wood, and needs added support. I have made finished paintings on a single veneer sheet, but they are finished when mounted to a thicker support or lighter cradled frame.

Composite Fiberboard

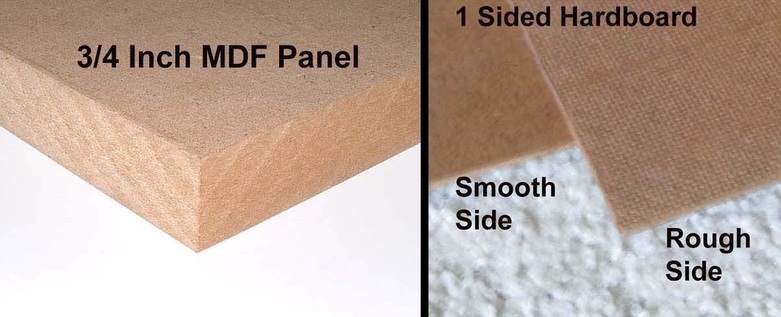

Composite fiberboard comes in various types, and there is no definite standard of manufacture between different mills. They are made from reconstituted wood pulp fibers glued together by a bonding agent, typically urea formaldehyde resin. The types of these best suited for painting are medium density fiberboard (MDF) or high density fiberboard (aka hardboard.) They offer large sizes and thickness, and a smooth uniform surface with no grain patterns, no surface or interior defects, at an economical price point. It machines well, and can be cut in unusual shapes and angles rather easily. Although it can also distort with added moisture, it does so uniformly, and tends to only curl rather than twist at the corners. Disadvantages are fiberboard being less structurally sound than solid wood, more susceptible to warping when thin, and is heavier than solid or plywood panels of the same size or thickness. MDF is often made from scrap wood material that is not necessarily of the highest grade, so it is thereby more acidic. Some types of MDF have little to no formaldehyde content, and can made from renewable material like wheat or straw. One particular distinction about MDF panels from hardboard is that larger thickness is available, up to about 4 inches. MDO (overlay) is MDF laid on a veneer plywood core, which combines the features of both.

Since hardboards are distinguished from MDF by having a higher density, which makes them stronger, they are more limited in width dimensions. They are manufactured using either a wet, dry, or wet and dry processing of the wood pulp fibers. In the wet process, wood fibers soak in a wet slurry so that they bond with their own natural lignin. This creates a smooth single side (S1S) with a noticeable screen pattern on the back. The wet/dry process works the same way except two smooth sides are combined, front and back (S2S.) The dry process involves using resins instead of water (MDF is made this way.) The manufacturers that supply hardboard panels for artists typically use the wet and dry in combination. This removes the wood lamella and water-borne chemicals, which makes for a better quality surface. The hot presses used in the manufacture also tend to leave behind traces of paraffin oil on the surfaces that can inhibit proper adhesion of paint or sizing, but this can be cleaned off with denatured alcohol. A disadvantage in hardboard is that it only comes in relatively thin widths of up to ¼ inch.

Do not misinterpret hardboard as hardwood. Hardboard can be made from high grade hardwoods but often is not, or is sometimes mixed with softwood. It is almost 100% wood content, whereas MDF contains about 5 to 7% resin. This can be processed to be lignin free with a low pH, which makes it especially useful for mounting paper. Hardboard options are tempered (darker) or untempered (aka standard.) Tempering adds surface strength and helps resist warping by repelling moisture. Early production of tempered boards were immersed in large vats of oil (often tung oil) which made it a poor choice for artists, in addition to the alternative of untempered boards being more fragile, so hardboards received a bad reputation as a surface for artworks. Now tempering is made with a small quantity of linseed oil (usually less than 3/10 oz per square foot) that is then baked into the panel to harden it. Sometimes no oil at all is used, only hardened resins. Again, remember that there is no real standard to manufacture, so there are many variables in the mix.

In Summary

So, with all this information, how does one make an educated choice selecting a wood panel? I personally would not recommend painting directly on MDF panels. As for hardboards, if the artist has a reasonable guarantee from the manufacturer that they are made with high quality materials, in my opinion they would be fine to paint on. Otherwise, I feel either type of fiberboard would function best when used only as a means of support for either paper or canvas, in which case restoration would be more easily accomplished should problems occur over time. I feel more confident painting on solid wood or plywood since it is easier to know what they are made of. Solid wood has size issues to consider, but is otherwise a fine choice, and there is no question as to its composition.

As an aside, I am the type of guy who likes to squeeze the tomatoes he buys, and it is worth mentioning that for mail orders I have made in the past, fiberboard panels rarely if ever arrive with any surface defects. However, I cannot always trust that solid wood or plywood orders I receive will have an unblemished surface or be perfectly square, unless I have great trust in the vendor, or I just go pick them out myself.

Some Web Resource Links:

US Forestry Wood Handbook

American Hardwood Species Guide

Composite Panel Association

Engineered Wood Association

Veneernet

Boulter Plywood

Ampersand Article on Hardboard Manufacture

Panel Processing Inc. (good Technical Bulletins in their Library section)

Books:

"Veneering: A Complete Course" by Ian Hosker

"Understanding Wood" by R. Bruce Hoadley

Composite fiberboard comes in various types, and there is no definite standard of manufacture between different mills. They are made from reconstituted wood pulp fibers glued together by a bonding agent, typically urea formaldehyde resin. The types of these best suited for painting are medium density fiberboard (MDF) or high density fiberboard (aka hardboard.) They offer large sizes and thickness, and a smooth uniform surface with no grain patterns, no surface or interior defects, at an economical price point. It machines well, and can be cut in unusual shapes and angles rather easily. Although it can also distort with added moisture, it does so uniformly, and tends to only curl rather than twist at the corners. Disadvantages are fiberboard being less structurally sound than solid wood, more susceptible to warping when thin, and is heavier than solid or plywood panels of the same size or thickness. MDF is often made from scrap wood material that is not necessarily of the highest grade, so it is thereby more acidic. Some types of MDF have little to no formaldehyde content, and can made from renewable material like wheat or straw. One particular distinction about MDF panels from hardboard is that larger thickness is available, up to about 4 inches. MDO (overlay) is MDF laid on a veneer plywood core, which combines the features of both.

Since hardboards are distinguished from MDF by having a higher density, which makes them stronger, they are more limited in width dimensions. They are manufactured using either a wet, dry, or wet and dry processing of the wood pulp fibers. In the wet process, wood fibers soak in a wet slurry so that they bond with their own natural lignin. This creates a smooth single side (S1S) with a noticeable screen pattern on the back. The wet/dry process works the same way except two smooth sides are combined, front and back (S2S.) The dry process involves using resins instead of water (MDF is made this way.) The manufacturers that supply hardboard panels for artists typically use the wet and dry in combination. This removes the wood lamella and water-borne chemicals, which makes for a better quality surface. The hot presses used in the manufacture also tend to leave behind traces of paraffin oil on the surfaces that can inhibit proper adhesion of paint or sizing, but this can be cleaned off with denatured alcohol. A disadvantage in hardboard is that it only comes in relatively thin widths of up to ¼ inch.

Do not misinterpret hardboard as hardwood. Hardboard can be made from high grade hardwoods but often is not, or is sometimes mixed with softwood. It is almost 100% wood content, whereas MDF contains about 5 to 7% resin. This can be processed to be lignin free with a low pH, which makes it especially useful for mounting paper. Hardboard options are tempered (darker) or untempered (aka standard.) Tempering adds surface strength and helps resist warping by repelling moisture. Early production of tempered boards were immersed in large vats of oil (often tung oil) which made it a poor choice for artists, in addition to the alternative of untempered boards being more fragile, so hardboards received a bad reputation as a surface for artworks. Now tempering is made with a small quantity of linseed oil (usually less than 3/10 oz per square foot) that is then baked into the panel to harden it. Sometimes no oil at all is used, only hardened resins. Again, remember that there is no real standard to manufacture, so there are many variables in the mix.

In Summary

So, with all this information, how does one make an educated choice selecting a wood panel? I personally would not recommend painting directly on MDF panels. As for hardboards, if the artist has a reasonable guarantee from the manufacturer that they are made with high quality materials, in my opinion they would be fine to paint on. Otherwise, I feel either type of fiberboard would function best when used only as a means of support for either paper or canvas, in which case restoration would be more easily accomplished should problems occur over time. I feel more confident painting on solid wood or plywood since it is easier to know what they are made of. Solid wood has size issues to consider, but is otherwise a fine choice, and there is no question as to its composition.

As an aside, I am the type of guy who likes to squeeze the tomatoes he buys, and it is worth mentioning that for mail orders I have made in the past, fiberboard panels rarely if ever arrive with any surface defects. However, I cannot always trust that solid wood or plywood orders I receive will have an unblemished surface or be perfectly square, unless I have great trust in the vendor, or I just go pick them out myself.

Some Web Resource Links:

US Forestry Wood Handbook

American Hardwood Species Guide

Composite Panel Association

Engineered Wood Association

Veneernet

Boulter Plywood

Ampersand Article on Hardboard Manufacture

Panel Processing Inc. (good Technical Bulletins in their Library section)

Books:

"Veneering: A Complete Course" by Ian Hosker

"Understanding Wood" by R. Bruce Hoadley